4 min read

The Evolution of Health Care Costs and Reimbursement

Performance Health Partners

October 19, 2020

Healthcare costs and forms of reimbursement have evolved over time. In the late 1800s, Samuel Clemons, whose pen name was Mark Twain, described a capitation-type payment for physicians in his hometown of Hannibel, Missouri. He wrote that his family paid their physician $25 per year to cover whatever illness they might have throughout the year. (1) Before the 1920s, health care costs were low and there was little need for health insurance. The biggest cost associated with illness was lost wages. In response, insurance policies akin to current disability insurance was born. (2)

From 1920 to 1930 healthcare costs began to rise as people moved from rural to urban areas and treatment of acute illnesses moved from family homes to hospitals. “These changes caused the price of medical care to rise as demand for medical care increased and the cost of supplying medical care rose with increased standards of quality for physicians and hospitals.” (2)

During this time period, Blue Cross and Blue Shield came into existence. A group of school teachers in Dallas, Texas “contracted with Baylor Hospital to provide 21 days of hospitalization for $6 per year” which eventually became the inspiration for Blue Cross. Prepaid hospital plans grew during the Depression, which provided cash flow to keep hospitals afloat. The Blue Cross plan allowed open access to quality hospitals. An insurance plan for physician services known as Blue Shield came along in the 1930s. (2)

The Growth of the Health Insurance Industry

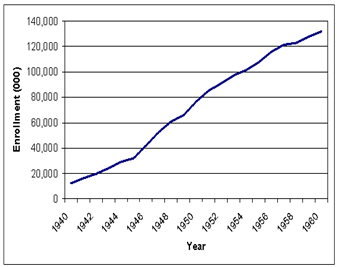

The health insurance industry grew from the 1940s through the 1960s as medical technology evolved and as the government encouraged the practice of including health insurance as part of employee compensation packages. (See Health Insurance graph)

Number of Persons with Health Insurance (thousands), 1940-1960

Source: Source Book of Health Insurance Data, 1965.

During that time, employers did not have to pay payroll tax on their contributions to employee health plans and employees did not have to pay income tax contributions to their health insurance plans paid by their employers.

In 1965 under the Kennedy administration, Medicare was put into place as a federal program with uniform standards of Parts A and B. Part A consisted of the compulsory hospital insurance program where persons were automatically enrolled when they reached 65 years of age. Part B served as a supplemental medical insurance for physicians’ services. At that time, physicians stood to benefit from Medicare by billing patients directly for a reasonable rate and then the patient was reimbursed by Medicare. (1)

Providing Healthcare Quality

The Health Maintenance Organization (HMO) Act of 1973 was enacted with the intention of containing costs and providing healthcare quality for populations that were previously underserved. “Fee-for-service medicine had led to health care inflation because it encouraged caregivers to maximize the number of procedures they perform, ignoring preventive care. Doctors and hospitals were not paid to keep patients well; they were paid to treat them when they were sick.” (1)

The Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (ACA) was later passed during the Obama administration. The Act was considered one of the most radical changes to health care in the US.

In 2015, the Secretary of Health and Human Services (HHS) and the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) directed “a move away from the traditional fee for service model and toward a value-based payment program that rewards quality of care over quantity”. (3) Pay for Performance (P4P) “ties reimbursement to metric-driven outcomes, proven best practices, and patient satisfaction, thus aligning payment with value and quality”. (4) Hospitals are not the only organizations impacted by P4P.

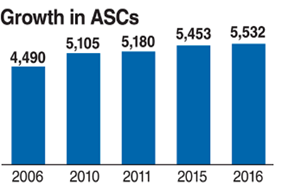

About 60% of surgeries once performed in a hospital are now performed in an ambulatory setting. (See ASC Graph 1)

In 2014, Ambulatory Surgical Center (ASC) Quality Reporting Program (ASCQR) began as a “pay-for-reporting, quality data program” developed by CMS. (5) ASCs are expected to report quality of care data for standardized measures in order to receive their full ASC annual payment rate. Ambulatory Surgery quality metrics include:

- Patient Burn

- Patient Fall

- Wrong site, wrong side, wrong patient, wrong procedure, wrong implant

- All-cause hospital transfer/admission

The Movement Towards Quality Measures

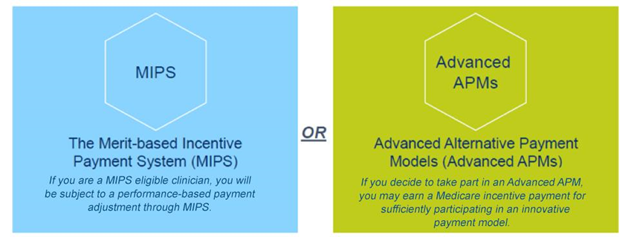

The Medicare Access and CHIP Reauthorization Act of 2015 (MACRA) was enacted to improve payments to physicians and other clinicians while rewarding value and outcomes via a Quality Payment Program. Eligible clinicians can participate as an individual or a group in one of two tracks: a. Merit-based Incentive Payment System (MIPS) or b. Advanced Alternative Payment Models (Advanced APMs). (See MIPS Graph 1).

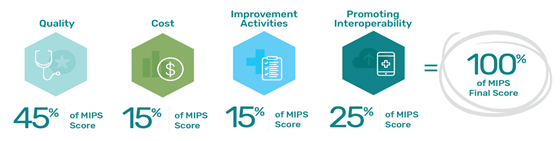

There are four performance categories in MIPS that can affect a clinician’s future Medicare payments. Performance categories are scored individually and have a specific weight that determines the MIPS Final Score. (See MIPS Graph 2).

Clinicians are expected to actively measure and report their quality measures. It is important to note that there are more than 250 quality measures in MIPS. Clinicians may report on “at least 6 quality measures, including at least 1 outcome measure or a high priority measure or report on a complete quality measure specialty or sub-specialty set”. (5)

The six domains for MIPS quality measures include:

- Patient safety

- Person and caregiver-centered experience and outcomes

- Communication and care coordination

- Effective clinical care

- Community/population health

- Efficiency and cost reduction

Once all data is submitted, Medicare payment adjustments for eligible clinicians are based on the MIPS Final Score. (See MIPS Graph 3).

MIPS Payment adjustments can be positive, negative, or neutral depending on MIPS scoring (6, 7).

Conclusion

As healthcare costs and forms of reimbursement have evolved over time, so have the models of care used by healthcare organizations. With the movement towards value-based care, organizations are now rewarded for providing high-quality care over quantity. This transition has driven organizations to achieve higher levels of patient safety and quality monitoring so that they can not only maximize reimbursement and maintain fiscal stability, but improve their outcomes in value-based care.

References:

1. Clemens S, Nieder C, editors. The Autobiography of Mark Twain. New York: HarperCollins; 1959. [Google Scholar]

2. Thomasson, M. Health Insurance in the United States. EHnet. Retrieved on October 21, 2019 from https://eh.net/encyclopedia/health-insurance-in-the-united-states/

3. Parker, D. (July 13, 2015). Pay for Performance vs. Fee for Service: Why You Should Care How Your Doctor Gets Paid. The Benefits Guide. Anthem. Retrieved on October 21, 2019.

4. “What Is Pay for Performance in Healthcare?”. (March 1, 2018). NEJM Catalyst. Retrieved on October 21, 2019 from https://catalyst.nejm.org/pay-for-performance-in-healthcare/

5. “ASC Quality Reporting”. CMS,Gov. Retrieved on October 24, 2019 from https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Quality-Initiatives-Patient-Assessment-Instruments/ASC-Quality-Reporting/

6. 2019 Merit-based Incentive Payment System (MIPS) Quality Performance Category Fact Sheet. Retrieved on October 24, 2019

7. Fact Sheet: 2019 Merit-based Incentive Payment Adjustments Based on 2017 MIPS Scores. Retrieved on October 24, 2019 fromhttps://qpp-cm-prod-content.s3.amazonaws.com/uploads/70/2019%20MIPS%20Payment%20Adjustment%20Fact%20Sheet_2018%2011%2029.pdf